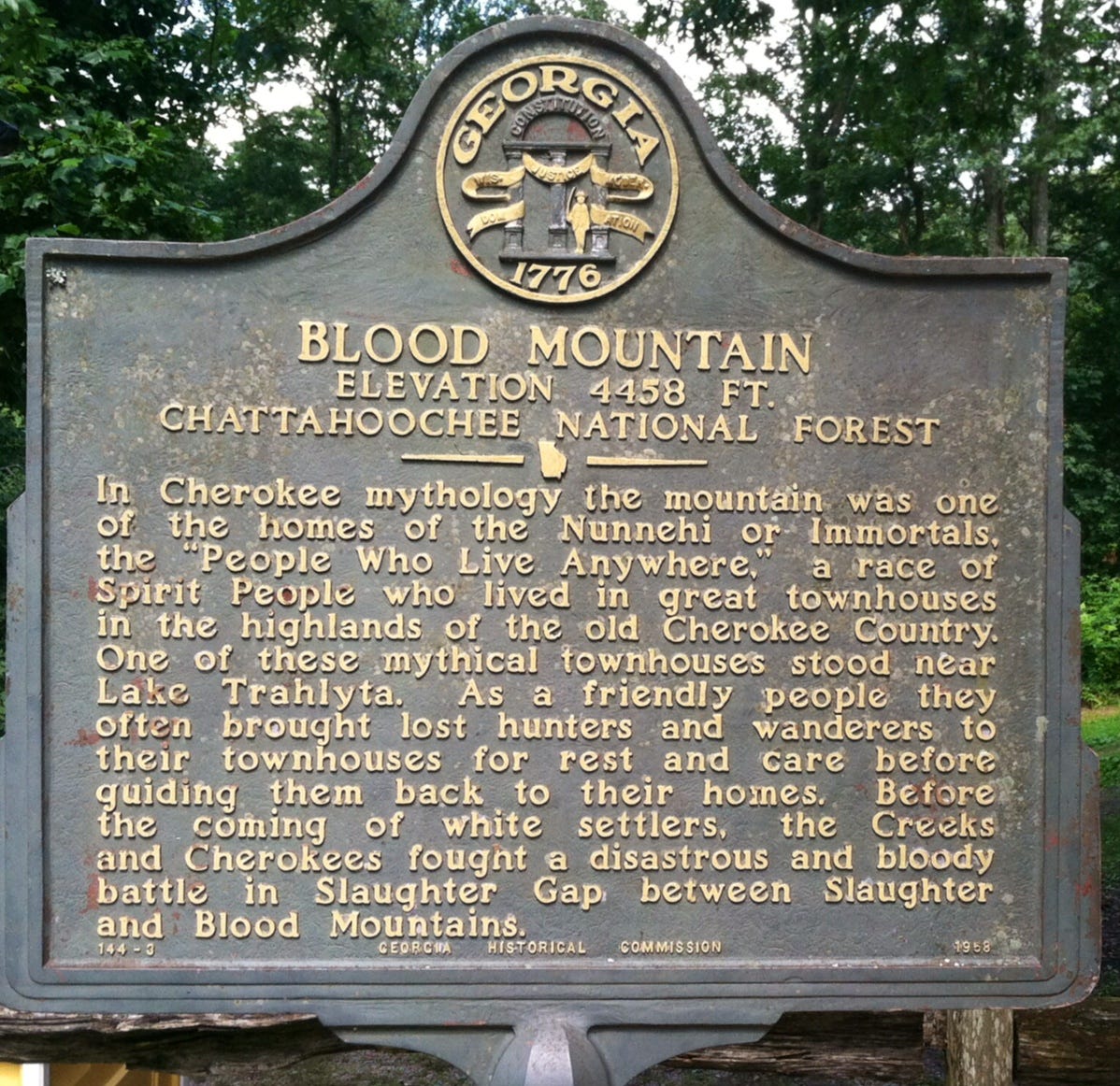

“In Cherokee mythology the mountain was one of the homes of the Nunnehi or Immortals, the ‘People Who Live Anywhere,’ a race of Spirit People who lived in great townhouses in the highlands of the old Cherokee Country. One of these mythical townhouses stood near Lake Trahlyta. As a friendly people they often brought lost hunters and wanderers to their townhouses for rest and care before guiding them back to their homes.” - Excerpt from a Georgia Historical Commission sign at the entrance to the Blood Mountain wilderness section of the Appalachian Trail

I recall the familiarity sensed when I first stood atop Preachers Rock, an overlook along the Appalachian Trail in north Georgia, at the 3,700-foot summit of Big Cedar Mountain. Like the calming awareness of returning home after two weeks’ travel, opening the front door, and appreciating that everything is as you left it.

An hour later, I met Tinkerbell.

“You smell bad,” she said. Her manner was without judgment; it carried no forcefulness. Instead of insult, the words brought relief; I was not alone.

I reasoned how I must have stunk to high heaven in the oppressive August heat and humidity. Then, with a less-than-bright grin, struggling to regain poise, I considered my state: dehydrated and hungry. Finally, I begged my stomach, Don’t throw up; please, whatever you do, don’t puke on this woman.

The view from Preachers Rock was everything I had imagined. And seemingly within reach were thousands of clouds, their intensity expressive of the radiance that escapes a 100-watt bulb. In their company, tens of thousands of evergreen trees, a lushness never properly expressed on painted canvas, provided a Myrtle-shaded canopy for the squirrel, deer, and wild turkey below. Preachers Rock was named after Joe “Bear” Lunsford, a local farmer and preacher who, in the late 1800s, would climb onto the rocky lookout and practice his sermons before Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

After she spoke, I noticed her beside matching hammocks, hanging wet clothes to dry on a section of rope knotted between two pine trees. She wore a smooth, flower-clad dress, symbolic of the counterculture from the 1960s, but unexpected attire for hiking the AT. The sweat along her headband dripped with repudiation for conventions. Her breasts, unaided by support, rested easily on her chest. Psychedelic-patterned socks, pulled high, that shouted everything but practicality, complemented a pair of sandals strapped to her feet. She might have been twenty-five, with long coffee bean-colored hair pulled gently from her face in a scruffy bun, not one blemish marked her sun-kissed skin. Beauty came naturally; she had no time for immaterial troubles like makeup or the latest fashion trend.

Before I answered the demand of my lower back to drop my pack, a soft voice began from one of the hammocks, “Momma.” The girl, no more than ten, momentarily rose to see whom her mother was speaking to, perhaps attempting to sort the visitor as friend or foe. Then, understanding that the weary traveler presented no harm, found sleep again.

“Are you ok?” the mother asked, looking into my eyes—a hint of caution in her voice. “You look beat.”

“Yes.” Before a hand was extended in friendship, it was wiped clean on my t-shirt. “My name’s Ryan; nice to meet you.”

Her grip was not guarded, lingering— “Welcome to the AT. I’m Sarah, but you can call me Tinkerbell. Out here, we go by our trail names. What’s yours?”

“This is my first hike on the AT; I’ve no trail name. But if I did, I’d want it to be EB – short for Epic Beard; until a month ago, that’s what I had.”

Tinkerbell gawked at my less-than-epic beard. “What made you shave it?” she asked, genuinely curious to have her question answered.

“Not too sure,” I said. “While brushing my teeth, I stared into the bathroom mirror, hesitant about what I saw. Minutes later, a set of clippers were in my hand; voila! Epic Beard no more. But, then again, it’s growing back somewhat. So, perhaps my trail name should be EBS – Epic Beard…Somewhat.”

Tinkerbell broke out: “It’s official, EBS, you shall be!”

“What brought you and your daughter here?” asked EBS with a genial smile, encouraging her to continue.

“The freedom from the distractions of city living is only found in the forest’s solitude. We prefer waking each morning to birds chirping, not honking car horns. Besides, my daughter needs to understand that it’s okay not to have control over one’s life; companies downsize, money gets tight, and sometimes daddies leave. The wilderness grounds us; it prepares us for life over the next ridge.”

“About that next ridge, how far is Blood Mountain?” After that, EBS added, “I’d like to make Neel Gap before dark.”

“Not far. ‘Bout three miles,” responded Tinkerbell. “You’ll make Neel Gap before sundown.”

His throat cracked: “Is there a stream close by?”

“There’s one about half a mile at the bottom of the side trail to our left, can’t miss it.”

The stream flowed leisurely, hopping over polished black stones; no sense of urgency was shown, steady. Pebbles whipped lightly in the shallow under wash, glittering like specks of gold in the sunbeams. EBS removed his shoes, socks, shorts, and t-shirt and, in underwear only, stepped cautiously from the bank, wading into the deep, immersing himself in the watercourse. Its temperature, at best, was forty degrees. Salty sweat, earthy grime, and the offensive stench that stained his bones were washed downstream, none of their ways to be remembered.

A rust-tinted Robin, perched high above suspicion, momentarily interested, watched as EBS filled his water bottle. Then, it turned its head slightly from right to left and flew away.

🖤🖤🖤